This article was written in collaboration with Liese Barbier, Teresa Barcina Lacosta, and Yannick Vandenplas.

Since the introduction of biosimilar medicines in the European market in 2006, biosimilars have made their mark in multiple therapeutic areas, including oncology, inflammation, hematology, and endocrinology (1). As of March 2021, the EMA has authorized over 65 biosimilar products and in the next 10 years, a considerable number of originator biologicals is expected to lose market exclusivity and be exposed to biosimilar competition (2,3).

Biosimilars have been safely and effectively used, exceeding a total clinical experience of 2 billion patient treatment days across Europe (4). Currently, biosimilars represent a 60% year-on-year growth in the share of the total biologics market in Europe, and this figure is expected to increase, based on the considerable number of biologics expected to lose market exclusivity in the next 10 years (3). Altogether, these data underline that biosimilars are here to stay. In this context, it is essential to ensure that the different stakeholder groups receive trustworthy and clear information about the principles and the value proposition of biosimilars.

Based on our research in this field (7, 8, 9), we offer recommendations on how to effectively educate healthcare professionals and patients about biosimilar medicines. This article asserts that increasing understanding about and trust in the efficacy, safety, quality, and value of biosimilars is a fundamental step toward a sustainable marketplace for biologicals, including biosimilars.

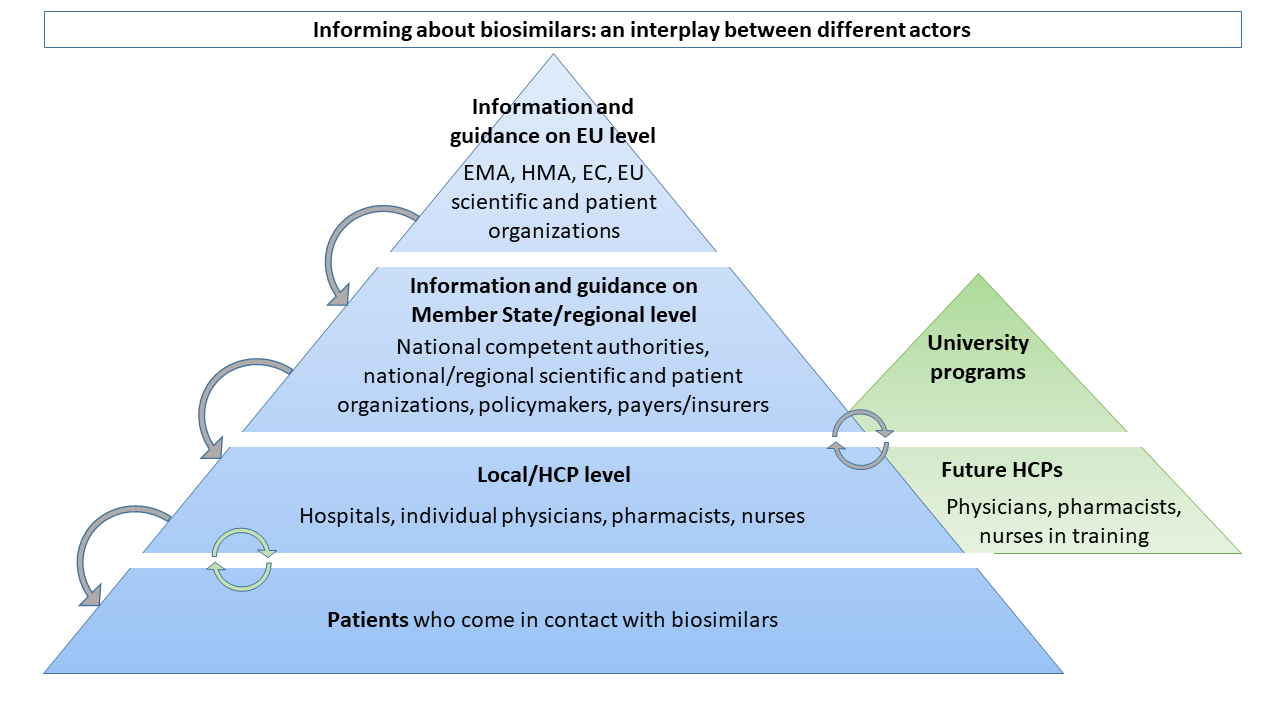

In Figure 1, we introduce the different levels at which information about biosimilars is provided by and communicated to the different stakeholder groups, illustrating that effectively informing healthcare providers and patients about biosimilars requires a well-directed interplay between various stakeholders.

Educating And Informing Healthcare Professionals About Biosimilars

Biosimilars are not well understood by many healthcare professionals and patients, which may have contributed to limited biosimilar use in some healthcare systems. Since the introduction of the first biosimilar in Europe, over 100 research articles with the aim of assessing the knowledge of healthcare professionals or patients about biosimilars have been published.7 Improvements have been observed over time, but generally low to moderate levels of awareness, knowledge, and trust of biosimilars persist in several European countries or regions. Stakeholder concerns mainly relate to uncertainty regarding the efficacy and safety of the biosimilar, and they have questions about concepts such as extrapolation of indications, immunogenicity, and interchangeability. This uncertainty is fortified by differences in definitions and concepts between, for instance, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It is our experience that papers originating from the U.S. often cannot be extrapolated to European countries (with mainly solidarity-based healthcare), as they have completely different healthcare systems.

Biosimilars pose a new development and evaluation paradigm, different from that of the originator biological, which appears to have fuelled uncertainties about biosimilar medicines among stakeholders. It is pivotal for healthcare professionals who are or will be using biosimilars in clinical practice to understand the paradigm underpinning biosimilar development and evaluation, which logically requires a shift in mind-set (10,11). In addition to this, the biosimilars knowledge gap may have been amplified by disparagement and dissemination of misinformation about biosimilars, intentionally or driven by misconceptions (7, 12, 13). Unfortunately, papers containing misconceptions still slip through the peer review and are being published (13, 14).

The variable knowledge and acceptance of biosimilars among healthcare professionals underlines the need for continued evidence-based information and education. Over previous years, several organizations have actively developed guidance, information, and educational materials about biosimilars for healthcare professionals. It appears, however, that the abundant available informational material does not effectively reach its target audience, as demonstrated by the continuing low to moderate knowledge and trust levels among healthcare professionals. New ways should be explored to leverage the existing material. In our research, we learned that passive education (on static websites) offers limited help. Effective healthcare professional education requires dynamic delivery of the messages. This can be done by involving and targeting stakeholders in a more active way and providing information tailored to the stakeholder group and therapeutic area (7). Effective information and education streams rely on collaborative efforts between the different stakeholders in the field, as outlined in Figure 1.

Educating future healthcare providers about biosimilar medicines and related concepts is equally important. Today in 2021, we have 15 years of experience with biosimilars, meaning informing healthcare professionals should become less dependent on post-graduate education. University curricula should provide up-to-date information and education about emerging therapies, including biosimilars. Healthcare providers, also freshly starting, should be equipped with the necessary knowledge and understanding about biological medicines, including biosimilars. Only then can they make adequate treatment decisions and counsel patients about their therapies. Misconceptions about biosimilars may in part stem from a lack of understanding of biological medicines and their inherent variability in general. Increasing understanding of biologicals at large should thus be aimed for during undergraduate training as well (7).

In addition to actively educating (current and future) healthcare professionals by means of targeted education programs and up-to-date university curricula, increased guidance about how to use biosimilars in clinical practice and shared best practices among peers may boost confidence. Here, key opinion leaders have an essential role to transfer experience and trust to their colleagues (7).

So far, information initiatives (and also research) have largely focused on healthcare professionals in the hospital setting. With the approval of biosimilars for subcutaneously administered products, biosimilars gain importance in the community pharmacy. Tailored information and education are needed to introduce primary care healthcare professionals (i.e., community pharmacists, general practitioners, and their staff) to biosimilars. Primary care healthcare professionals may especially benefit from active guidance and supporting materials about biosimilars, as there is no hospital network to support them with biosimilar initiation or switching. As differences may exist in injection devices between self-administered reference and biosimilar products, primary care professionals need to be well trained to counsel patients about those differences.

In the end, the multidisciplinary patient care team (i.e., the treating physician, pharmacist, nurses, and supporting staff) needs to be well equipped to collaboratively and adequately inform, transfer trust, and counsel the patient about their biosimilar therapy.

Educating And Informing Patients About Biosimilars

Patients are a large and diverse group, of which previous research has shown that perceptions and understanding about biosimilars are, not surprisingly, rather limited (7,9). Educating patients is important to provide clarity and avoid misinformation about biosimilars once they are introduced to them (13). Especially in the context of transitioning therapies from the original biological medicine to its biosimilar, the importance of adequately informing patients should not be underestimated. Likewise, it is important to help patients find trustworthy information on the internet, as there is – as with any topic – an abundance of noise and fake news out there. Patient organizations could play a critical role here (9). Clinical research has already shown improvement in patient outcomes after correctly informing patients during transitioning (15,16). In this context, correct communication with the patient is particularly important to avoid nocebo effects – the worsening of symptoms or an increase in side effects associated with a negative attitude toward a medical therapy, in this case the biosimilar. The lack of knowledge and understanding about biosimilars has been described as the main underlying reason for the occurrence of nocebo effects, possibly leading to treatment failure (17).

Former research has shown that communication about biosimilars to the patient should be tailored to the individual’s needs, in a way that is understandable positive, with one voice, and supported by audio-visual material (9). Not every patient will require the same amount of information about their treatment, so it is important to tailor the information to the individual’s needs. In order to avoid misconception and confusion among patients, all information should be consistent across resources. In other words, stakeholders must speak with one voice. Various stakeholders have an important role to play in this process, from regulators to healthcare providers, as shown in Figure 1.

In many European countries, treatment decisions are based on shared decision-making between patients and their physician. This is known to benefit patient outcomes in terms of treatment adherence and thus the adoption of biosimilars into clinical practice. However, a necessary condition for successful shared decision-making is the provision of correct information to patients.

In recent years, various stakeholders have already developed informational or educational material about biosimilars for patients (9). So, there is certainly sufficient high-quality material already available for patients, as is the case for healthcare providers. However, the main difficulty seems to be reaching the patient. Patient associations play an important role here as an engaged and independent source of information for patients. The material already developed should therefore be used as a starting point for patient associations, rather than reinventing the wheel themselves.

We would also like to draw attention to the fundamental difference between informing patients and healthcare providers. Healthcare providers (i.e., physicians, nurses, pharmacists) have a duty to become sufficiently familiar with what biological medicines, including biosimilars, are. They are responsible for correctly informing patients about their treatment on a daily basis. This is in contrast to patients, where it would be unnecessary and undesirable to inform all patients about biosimilars. After all, only a subgroup of patients will encounter biological therapies. The aim must therefore be to inform patients who actually need this information, in other words, patients who come into contact with biosimilar medicines.

Conclusion

Informing and educating healthcare professionals and patients about biosimilars are essential to biosimilar adoption. Close collaborations between regulatory authorities, scientific and professional associations, universities, patient organizations, payers, and policy makers on both the European and national member state levels are important to effectively disseminate information about biosimilars and concepts related to their use. We conclude with four overarching ways to effectively inform and educate patients and healthcare professionals about biosimilars:

- The abundant available information and education material about biosimilars should be leveraged by means of a more (inter)active dissemination to patients and healthcare professionals. A central (European) repository would be very helpful to facilitate retrieval.

- Misinformation in the biosimilar arena should be challenged. Regulatory authorities and other stakeholder groups should dispel misconceptions by continuously providing balanced and unbiased information. The same central repository could be a home for that.

- University curricula should be reviewed and renewed where needed to provide up-to-date education about biological medicines, including biosimilars, for future healthcare professionals.

- For both patients and healthcare providers, information should be tailored to the stakeholder group, therapeutic area, and the individual’s needs. As with any therapy, a one-size-fits-all solution does not exist.

The biosimilar concept is complicated, and communication skills may play a crucial role in getting the right message across. However, it is imperative to have the science right in the first place, and then focus on an attractive packaging tailored to the target audience.

Written by Liese Barbier, Teresa Barcina Lacosta, Yannick Vandenplas, Arnold G. Vulto, Department of Clinical Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapy, KU Leuven

References

1. European Medicines Agency and the European Commission. Biosimilars in the EU - Information guide for healthcare professionals [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/leaflet/biosimilars-eu-information-guide-healthcare-professionals_en.pdf

2. European Medicines Agency. Biosimilar medicines: Overview [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Dec 30]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/biosimilar-medicines-overview

3. IQVIA. The Impact of Biosimilar Competition in Europe [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 16]. Available from: https://www.iqvia.com/library/white-papers/the-impact-of-biosimilar-competition-in-europe

4. Medicines for Europe. Biosimilar medicines. Infographics [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.medicinesforeurope.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/BIOS5.pdf

5. Biosimilar Development. Samsung Bioepis Releases ‘Education In Biosimilars’ Whitepaper, Exploring The Need For Better Education On The Innovation, Quality And Value Of Biosimilars [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.biosimilardevelopment.com/doc/samsung-bioepis-releases-education-biosimilars-whitepaper-innovation-quality-biosimilars-0001

6. Samsung Bioepis. Education in Biosimilars Whitepaper [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.samsungbioepis.com/upload/attach/Samsung Bioepsis whitepapter_V4.pdf

7. Barbier L, Simoens S, Vulto AG, Huys I. European Stakeholder Learnings Regarding Biosimilars: Part I—Improving Biosimilar Understanding and Adoption. BioDrugs [Internet]. 2020;34(6):783–96. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00452-9

8. Barbier L, Simoens S, Vulto AG, Huys I. European Stakeholder Learnings Regarding Biosimilars: Part II — Improving Biosimilar Use in Clinical Practice. BioDrugs [Internet]. 2020;34:797–808. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00440-z

9. Vandenplas Y, Simoens S, Van Wilder P, Vulto AG, Huys I. Informing Patients about Biosimilar Medicines: The Role of European Patient Associations [Internet]. Vol. 14, Pharmaceuticals. 2021. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/ph14020117

10. Weise M, Bielsky M-C, De Smet K, Ehmann F, Ekman N, Giezen TJ, et al. Biosimilars: what clinicians should know. Blood [Internet]. 2012 Dec;120(26):5111–7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-04-425744

11. Gonzalez-Quevedo R, Wolff-Holz E, Carr M, Garcia Burgos J. Biosimilar medicines: Why the science matters. Heal Policy Technol [Internet]. 2020;9(2):129–33. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/deref/https%3A%2F%2Fdoi.org%2F10.1016%2Fj.hlpt.2020.03.004

12. Building a wall against biosimilars. Nat Biotechnol [Internet]. 2013;31(4):264. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2550

13. Cohen HP, McCabe D. The Importance of Countering Biosimilar Disparagement and Misinformation. BioDrugs [Internet]. 2020 Jul; Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-020-00433-y

14. Bourdage P. Facts matter and the truth is worth fighting for [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/facts-matter-truth-worth-fighting-pierre-bourdage/

15. Tweehuysen L, Huiskes VJB, van den Bemt BJF, Vriezekolk JE, Teerenstra S, van den Hoogen FHJ, et al. Open-Label, Non-Mandatory Transitioning From Originator Etanercept to Biosimilar SB4: Six-Month Results From a Controlled Cohort Study. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ) [Internet]. 2018 Sep;70(9):1408–18. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.40516

16. Tweehuysen L, van den Bemt BJF, van Ingen IL, de Jong AJL, van der Laan WH, van den Hoogen FHJ, et al. Subjective Complaints as the Main Reason for Biosimilar Discontinuation After Open-Label Transition From Reference Infliximab to Biosimilar Infliximab. Arthritis Rheumatol (Hoboken, NJ) [Internet]. 2018 Jan;70(1):60–8. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/art.40324

17. Kristensen LE, Alten R, Puig L, Philipp S, Kvien TK, Mangues MA, et al. Non-pharmacological Effects in Switching Medication: The Nocebo Effect in Switching from Originator to Biosimilar Agent. BioDrugs [Internet]. 2018 Oct;32(5):397–404. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40259-018-0306-1

This article was first published as a guest-column on Biosimilar Development on 31 March 2021